- Sources

- Information Gathering

- Citations and Citation Management

- Final Remarks

- See our other Research Posts below!

Sources

Research is the synthesis of evidence from assembled sources to derive information about the past or present. Any researcher worth their salt draws conclusions from the most reliable sources available, taking into account the biases of each and their historicity. All sources will have bias, the skill comes from being able to navigate those biases to draw reasonable conclusions. Primary sources are those that personally attest to a subject. Secondary sources are derived from primary sources and are typically a synthesis of multiple primary sources.

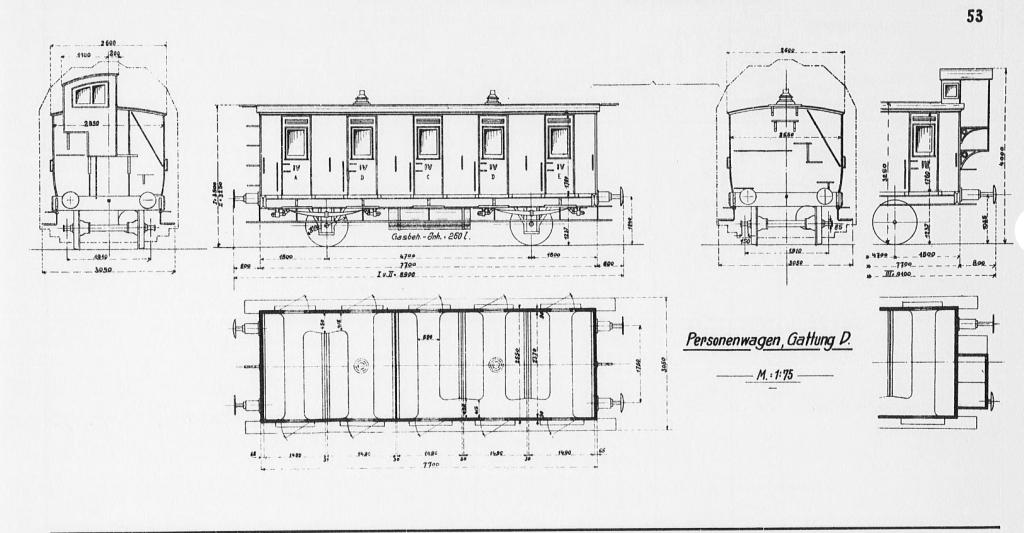

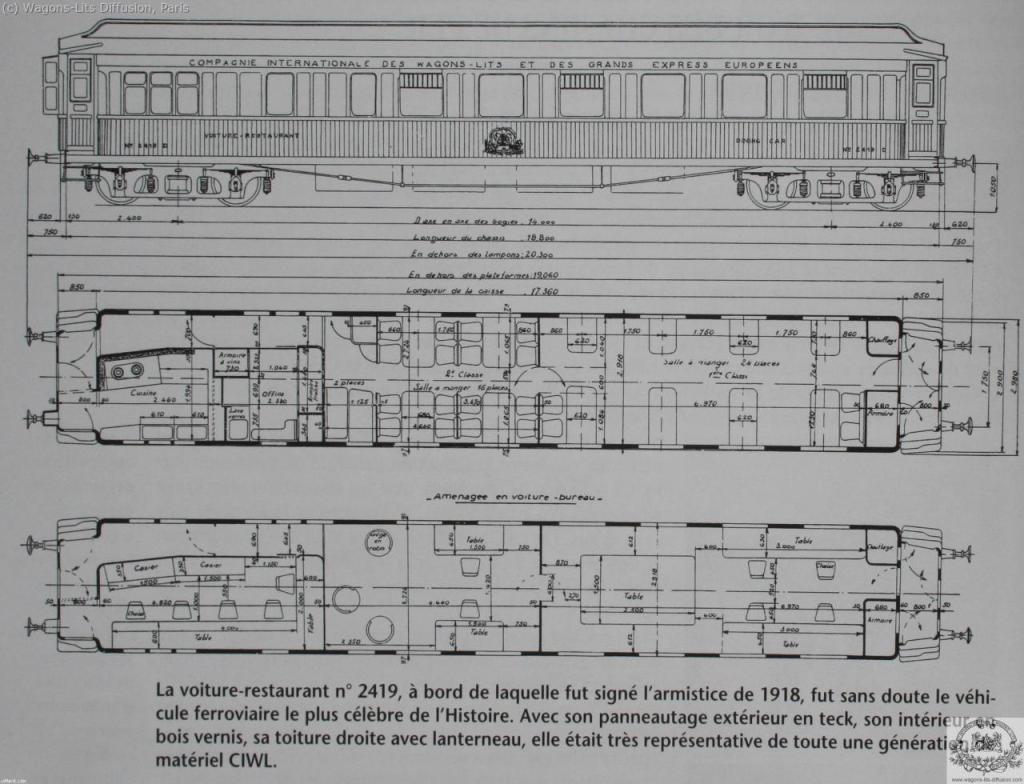

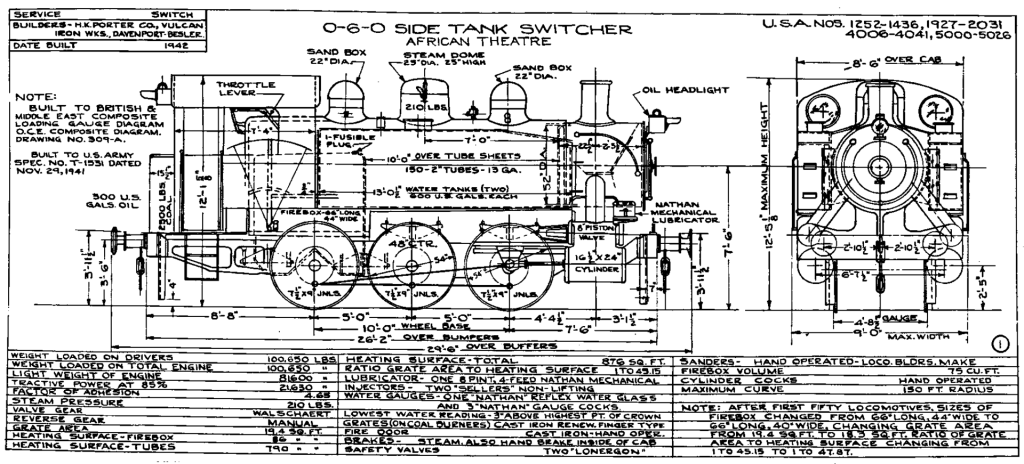

Plans

Often, railway modelers will look for plans from which to have their art perfectly imitate life. When it comes to locomotives and rolling stock, modelers typically find one of three resources: Folios, Erecting Cards, or Modeling Diagrams. The following section is based upon Daniel Gollery of Studio 346’s outline.

Folio

Folios are a primary source made during the service life of a piece of equipment. The measures included in them are absolute and measured directly from stock, though the folio itself frequently may not be drawn to scale.

Erecting Card

Erecting cards are also primary sources. They are drawn to scale and made during construction for component assembly. Detail of certain components is frequently implied, as the purpose of the document is for product assembly, not part production.

Modeling Diagram

Modeling diagrams are not primary sources. They are drawn independently by scale modelers for the creation of scale models. They will frequently include estimations based on other sources but should not be trusted as a reliable source of dimensions. While they may be designed from erecting cards or folios, they can also be conjecture based on photographs, textual evidence, verbal accounts, or wild supposition.

Like Wikipedia, modeling diagrams can be useful; one could consult listed sources for their own purposes. However, one should also do their due diligence to weigh the reliability of the listed sources before taking them as evidence.

Of course, locomotives and rolling stock aren’t the only things someone may want to model. Buildings, right of way, catenary, and the tracks themselves are frequently the subject of research.

Ephemera

Ephemera are typically primary sources meant to be disposable and widely disseminated; tickets, timetables, postcards, and fliers are all examples of ephemera. For railway historians, ephemera can be an important part of research. Tickets can reveal routes, timetables can reveal average track speeds and cargoes along a route, and advertising can reveal goals of railroad companies.

Photographs and Videos

Some say a picture is worth a thousand words; photos can be an important tool for examining railway history, especially in the absence of textual sources. You certainly don’t need me to tell you that, but it’s important to keep your eyes open when examining photos or video. Captions and metadata for photos usually centers around the subject, whatever is in focus, but photos can have lots of information waiting in the background. A photo of a locomotive may also have the elusive detail you need about a station building, or an example of a railway uniform, even when the subject is a locomotive.

With an idea of what we may be looking for, the question becomes where to look!

Information Gathering

Databases

Databases are where data is based; fairly straightforward. They can come in a variety of forms and can be free of charge or paid access. For paid access, they can be subscription based or a one-time-fee for single articles or entire collections. It’s important to note that many paid access databases can be accessed for free through other institutions, like libraries.

Catalogs

Catalogs are often the first step in finding sources, they’re your map to navigating databases. Catalogs tend to have more granular means of locating and filtering information and are a compressed method of access. They do not hold the actual items, but will usually include item metadata; creation date, provenance, description, name, and location. As an example, you may search WorldCat for your railway of choice; it will return results and tell you where you can borrow the title from, but you cannot read a book on WorldCat directly.

Collections and Repositories

Collections refer to an assemblage of items held by a person or institution. They have the actual items that are the subject of interest and are referenced by catalogs. These can take the form of online image repositories like Eisenbahnstiftung or BahnBilder, physical collections like Locomotion Shildon, or online repositories with representations of physical artifacts like the National Railway Museum’s collection online.

The Search

Jacob, you’ve been going on about where one might find something but not how to find it.

It depends. (Drink!) Start with a catalog or search service; search engines and Wikipedia can be genuinely helpful starting points. With Wikipedia, we’re going to skim at best and then jump down to the bottom of the page, to sources! Here, one can find the photo credits, books, journal articles, news publications, and other sources that folks used to make the Wikipedia article. If a source cited is a secondary source, it should have sources of its own, which can help you track down more evidence! This is what we in the field call “a rabbit hole.” (Note: If it isn’t a primary source and doesn’t have sources of its own, treat it with a hefty dose of skepticism.) These sources are often stored in some kind of database or collection, which can help clue you in on the taxonomy that can help you navigate catalogs to find even more sources.

Taxonomy? What are you talking about?

Taxonomy is how information specialists categorize information. For example, your search for photos of a K.Bay.Sts.B S 3/6 locomotive returns some hits; one photo has the tag “Bavarian railway,” another has the tag “Länderbahnzeit,” and a third has “Br.18.” Each speaks to a different kind of categorization; the first is based on railway, the second based on time period, and the third is based on locomotive class after a major change in organization. Each is a sensible way to categorize a photo of an S 3/6, by using these tags as search terms, you can find more photos of what you want. You can also combine them to get more precise search results!

Okay, how do I combine them? I wrote them all and got no results.

That depends on your search method and what catalogs you may be using. Many search systems employ some kind of Boolean logic (AND, OR, NOT), others may have separate filters or may only support searching title text. Where applicable, this is where you should consult a reference librarian, who can help you create search strings to narrow your results. Sometimes, collections will also have guides to help you understand how to navigate the collection; these often, though not always, have tips on using search functions. It also doesn’t hurt to try some common search techniques any time you’re using a search feature.

Citations and Citation Management

So, you have some evidence, excellent! Now what? We’ve examined primary and secondary sources and discussed some on how to gauge their validity; however, it’s important to be transparent about the validity of your own research via citations. Citations give credit to the sources you use and provides justification for the conclusions you’ve drawn. For those scientifically minded, these are the elements that allow others to repeat your ‘experiment’ to evaluate your results.

As a historian trained at a University of California, my preferred way to cite sources is according to the Chicago Manual of Style. Others may prefer APA (American Psychological Association), MLA (Modern Language Association), Harvard, or any other number of citation styles. You may have to tailor your citation styles to the media you publish your findings in. For example, Chicago footnotes don’t work in an audio-only medium. While I won’t dive into the actual details of citation styles here, the crucial elements of your citations must be detail and consistency. Stick to one citation style in your research and ensure those citations have enough detail for others to find the exact sources you used. Citations should include who created the source, its name, its date, and where someone can find that source.

The more sources you consult, the longer your list of citations, and the more complex it becomes to properly attribute them and keep track of your findings. For this, academics have created various citation management systems. Zotero, Mendeley, and EndNote are the most popular options; Zotero is open source while Mendeley and EndNote are paid options. Zotero is my preferred system and integrates well with GoogleDocs, Microsoft Word, and LibreOffice Writer (though not with Microsoft 365 Online). These citation Management systems often allow you to upload sources to be accessed directly through the manager, allow you to create your own tags and taxonomy, and allow you to leave notes so you can remind yourself of relevant information, like page numbers or timestamps. Additionally, they can help you format your citations (but should not be used in place of your own understanding and judgement!)

Final Remarks

Obviously, my brief overview is no substitute for experience or a four-year degree. However, it’s my firm belief that giving people the tools to get started in their own research helps to shine light on even more unique corners of the hobby and help folks gain extra appreciation for the history of European railroading.

That was a lot to unpack, and I think I lost a lot of the details. Could you explain all that some other way?

Not to worry! I’ve also documented an example research process, so you can follow along on that instead!